While Drug Court saves more than $13,000 a year between the cost of incarceration versus the cost of treating someone’s addiction, there’s more at stake than money.

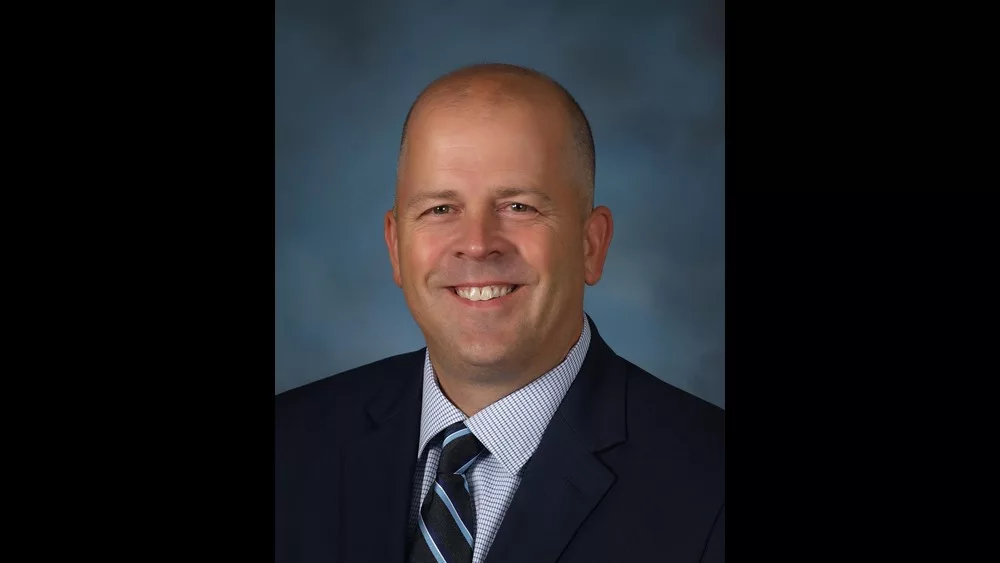

It’s someone’s life and well-being on the line, and that was the message during Tuesday’s Cadiz Rotary Club meeting — when 56th Judicial representatives in Program Coordinator Jessica Board, Regional Supervisor Janice Cunningham and District Judge Jamus Redd discussed the intricacies of local Drug Court.

On the surface, rampant, non-violent drug use often creates this predisposition of failure — and suddenly, someone runs out of chances with family, friends or employment.

Enter Drug Court, a voluntary option for those in need of intervention and criminal diversion during the probation and shock probation periods.

But as Board, Cunningham and Redd can attest, it’s more than just passing a couple of drug tests and a slap on the wrist. Typically an 18-to-24-month intensive personal program, it’s a complete reset of one’s life.

Among its many stipulations, someone in Drug Court must pass a GED exam if they haven’t graduated high school. They must pay back restitution and prior court costs, gain full-time employment, find sober housing, pay child support (if applicable) and work toward custody/visitation rights of their children, attend mental/addiction help clinics such as “AA” and “NA,” visit with a volunteering Drug Court judge once a week, submit to two drug tests per week, work with Pennyroyal Mental Health, and maintain a regular calendar of visits with program and regional coordinators.

Board, who took over for the retired Doug Martin in June, said the two most difficult steps of the graduation process might be finding good housing and good jobs — often based solely on tough referrals.

Cunningham said the connections with certain agencies and employers have helped connect people with clean housing and good jobs, but more could be done. The supervision of Drug Court is tighter than typical probation and shock probation paths, and Cunningham advises that participants cannot graduate without a stable job and a stable home in hand.

Redd said there’s deep penalties for failing Drug Court once admitted into the program, because it can be seen as evading punishment.

In the last 20 years of operation, and 16 years in Trigg County, Cunningham and Board both said cases from all walks of life have come through the doors — needing help with depression, anxiety, childhood or adult trauma, medical dependency, classic alcoholism and other tough paths.

And if you think addiction is difficult, ask Board yourself. She’s 15 years clean, but admittedly didn’t let her problems reach a Drug Court level.

Since the program’s inception, more than $125 million has been saved in tax dollars, and since 2018, 22 participants have graduated from this district’s program, with more than $6,100 paid in restitution.