More than a century ago, the oil and gas boom swept across Kentucky — from the eastern Appalachian mountains, all the way to the marshes of the Jackson Purchase.

In 1922, oil was specifically discovered in Hopkins County near Mortons Gap — only confirming the underground wealth of “black gold” once located in the Pennyrile.

Fast-forward to Spring 2023, and the mad rush for a quick buck has its price.

During his Thursday afternoon “Team Kentucky” update, Governor Andy Beshear announced that through the “Better Kentucky” Plan and the federal “Bipartisan Infrastructure Act,” the state will be using $25 million to plug orphan wells across the state — with the possibility of employing more than $75 million in grants.

Beshear said more than 350 such wells have already been plugged in 14 counties: Cumberland, Christian, Daviess, Henderson, Lee, McLean, Ohio, Pulaski, Webster, Estill, Lawrence, Powell, Warren and Union.

Beshear thanked the Energy & Environment Cabinet, as well as the Oil & Gas Association, for their efforts — because “they began work long before” the federal guidance and before the monies were released.

But what exactly is an “orphan well”?

According to the Environmental Defense Fund, once oil and gas well are done producing, they must be properly closed and capped in order to further prevent air and water pollution, while protecting surrounding communities from devalued properties at best, and climate-changing methane emissions at worst.

Open to groundwater sources and nature, these wells often times have been disruptive for a century or more. With owners of record either insolvent or long gone, cleanup and liability falls specifically to state and/or federal agencies.

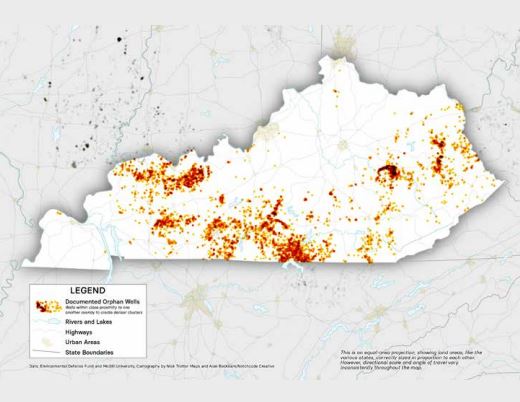

By then, these “orphans” have already impacted Kentuckians. Left alone, the state at one point had more than 14,300 such wells causing problems.