For the past two weeks, two questions have been on repeat in barber shops, bars and boutiques, alike.

“How about this weather?” And: “What’s the buzz? Tell me what’s happening.”

The first query is simple: spring has always been in like a lion, and out like a lamb in south western Kentucky. That’s never going to change.

But the second query? Well, the incessant song of the cicada — a crunchy insect with big, bright red eyes — brings with it a bit more difficulty.

This was the particular stanza at West Cadiz Park in Trigg County last Thursday afternoon — a cacophonous racket ambient enough to drive dogs and local denizens into borderline delirium.

Earlier last week in Clarksville, Tennessee, Austin Peay State University entomologist Dr. Donald Sudbrink held court to a full house during the season finale of “Science On Tap” at Strawberry Alley — offering deep analysis on this slumbering orthoptera that has awakened by the billions, and beleaguered the peace and quiet not just of the News Edge listening area, but the entire Midwest and eastern seaboard.

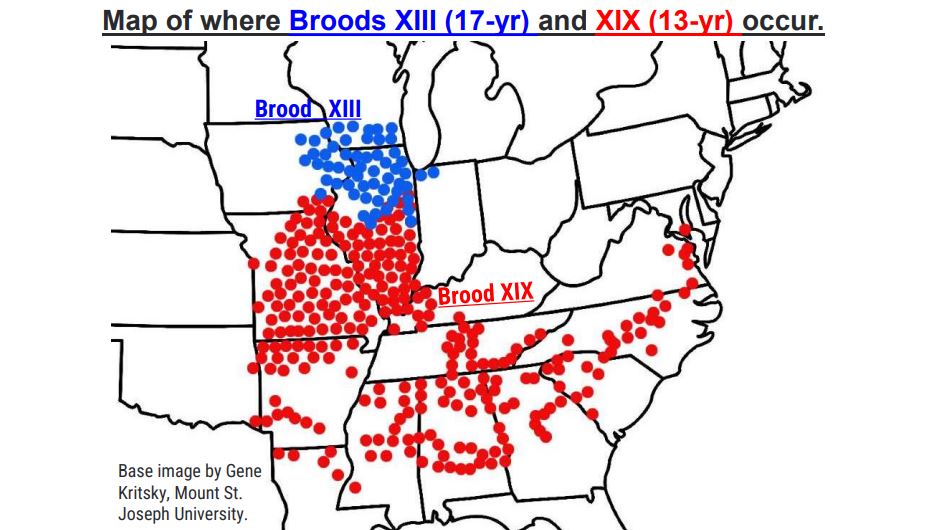

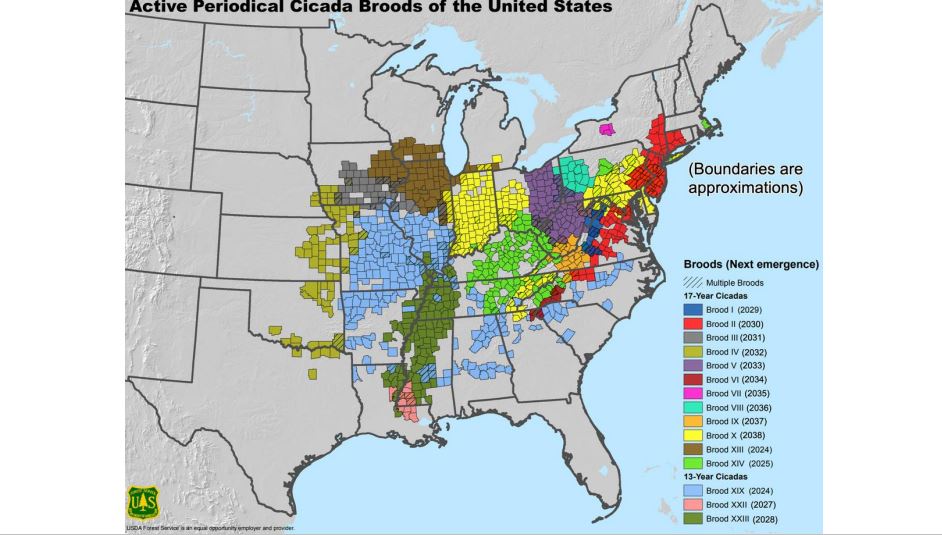

“Brood 19,” he said, is what many are experiencing right now — a 13-year cicada that last emerged from deep earthen roots in 2011. With nearly 1.5 million insects expected per acre, this year’s cicada population — paired with the northern Illinois 17-year “Brood 13” — could reach more than 1 trillion, with one goal in mind.

Survive at all costs.

Sudbrink noted this “satiation” evolutionary tactic allows for the non-locust species to reproduce and return later return back into the ground for “hibernation.” Once they enter the food web, however, everything changes.

Like a rare treat, they are currently the favorite foods of birds, cats, dogs, fish, snakes, squirrels, frogs, small mammals, other insects, and, occasionally, humans. In 2021, more than 80 bird species switched their diets away from forest caterpillars to cicadas — allowing this worm to damage wooded groves.

“Mostly harmless,” however, doesn’t mean “model citizen.” With their large clutches of eggs and dietary habits, cicadas can damage tree branches, and small, fruit-bearing orchards should especially be protected with quarter-inch fine mesh cover.

Furthermore, pets that ingest too many of the “nut-like” nymphs and their molten exoskeletons could get upset stomachs, while humans that ingest them — perhaps through a jambalaya, gumbo, garden salad or protein-rich cookie — while possessing shellfish allergies should call a physician.

But to think eating cicadas, or many other insects, is “gross,” he said, might not be a fair assessment. More than 2 billion people worldwide have insects in their regular diet, and 80% of the world eats them “occasionally.” The demand for animal protein, especially in arid climates, is up 75% in the last decade — and it’s not uncommon for livestock to partake of the nutrient-rich invertebrates.

What’s more, Sudbrink added, is that over the millennia, and despite these clever survival tactics, there used to be more cicadas than there are now — 23, or more, broods, down to 15, because of different extinction events.

“Brood 23,” which can also be found in northwest Tennessee and south western Kentucky, is another 13-year cicada expected to emerge in 2028. “Brood 19’s” next visit should be in 2037.